By: Steven Kantor

Typical greeting card sentiments

just don’t capture the joys and disappointments of being a father of a child

with autism. My youngest son Ari, now

18, was diagnosed with autism at 23 months.

I dream of designing a greeting cards line for families with

autism. Something like: “Happy Father’s

Day! I know being my father isn’t

easy. Thank you for standing by

me.”

Ari is a happy guy seemingly

untroubled by his condition. On the

other hand, I’m painfully aware of his differences and work hard to connect

with him – a humbling exercise that occurs every day. Ari’s struggles with

autism have been transformative. I’ve

learned that it’s really not Ari’s battle; it’s mine.

I’ve had breathtaking successes and profound failures. I’ve learned much

about autism and even more about my limitations as a parent. My initial feelings of loss about not being a

traditional dad to Ari have been complicated by my awe at the range of human

interaction.

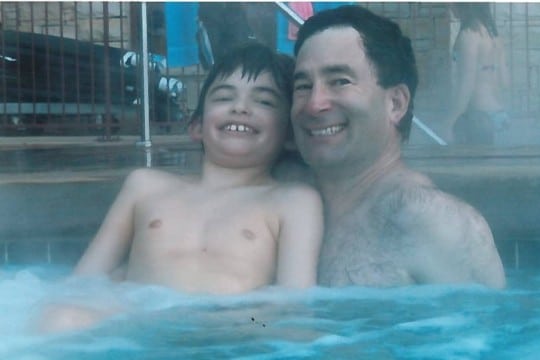

My first big breakthrough came

when Ari was six. I had tried all the

classic routines that had enabled me to successfully connect with my typically

developing son with no success. Then

Ari’s mother called me one day in tears.

A child enrolled in a school for children with autism had wandered off

and drowned in a pond. Somehow, we agreed that I had to teach Ari how to swim.

Did I mention that I sink like a stone?

That getting in a swimming pool is source of anxiety in the most personal of

ways? That I would do anything to avoid

the water? How was I going to teach a

child to swim that doesn’t even speak?

My anxiety, I’m sure, was channeled

to Ari as we got ready to go to the pool that first day. Ari started crying when we left home and

continued wailing as we got into the taxi, walked through the community

center’s lobby, got on the elevator, changed into our swimming suits, and entered

into the pool. My confidence that I was

doing the right thing for Ari was challenged by his absolute misery. Our fellow

swimmers were initially tolerant -think of a crying baby on an airplane- but after

the third week, one woman came up to me and asked me whether I enjoyed abusing

my child. Other people turned away from me like a pariah. After a few weeks, I

noticed that the pool cleared out when we arrived.

The first step was getting in the

pool. Do we use the ladder, jump in, or

dip our toe to test the water? Ari

didn’t like any of the options and often I was left freezing in the pool while he would be wailing on the side. Trying to think outside the box, I had

read an article about people with autism having sensory issues, so I went out

and found wet suits for the both of us. Of

course, the wet suit itself only compounded the sensory issues as well, but it

was the better of the two evils. The

wet suit made him warm; we could now focus on the challenge of getting into the

wet suit as a diversion to getting in the pool.

The wet suit also helped with his buoyancy. Note to self, wet suits don’t look so great

on middle aged men.

To say that progress was slow is

an understatement. There were many weeks that we seemed to go backwards,

literally and figuratively. But after

six months, I learned two very important lessons. I knew that Ari was a visual

learner, so I had focused on demonstrating the appropriate techniques. I

discovered that Ari had difficulty processing left and right images. In other

words, if I wanted Ari to lift his right arm, I had to face him and lift my

left arm. This was an “aha” moment. The

second lesson was the necessity of finding a re-enforcer, a goal to shoot

for. For both of us, it was the ability

to go from the “cold pool” to the “warm pool”, a 2 foot deep warming pool

designed for people with physical disabilities.

This was a goal we could both share and celebrate at the end of the

hour. There were many moments when we both raced

to the warm pool, got in and giggled together.

There were also moments when I would look at him and ask myself “What am

I doing?”

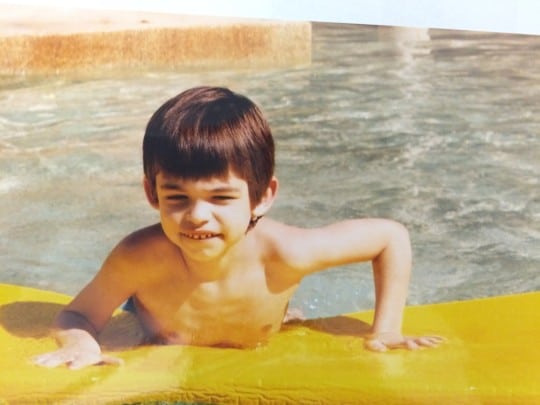

It would be nice to report that

Ari learned how to swim and now we happily go swimming together. Part of that

is true. Ari somehow learned to swim and

loves it; I still hate to go near a pool. But I like to think that facing our swimming

challenges together created an unspoken, but binding, connection. I have used the lessons of swimming to teach

Ari to play tennis, hit a golf ball, ride a bike and throw a football. I have been able to share a part of me with

my son with autism in ways I couldn’t imagine.

I have learned that what I thought were limitations are truly opportunities

to cherish, even if they may not be solved in conventional ways. Looking back, I marvel at his commitment and

tenacity towards solving problems he seemingly doesn’t understand.

I am incredibly grateful for the

privilege of being a father to both of my sons, an experience that I will

treasure for the rest of my life. That is the only gift I need for Father’s Day. I wish all the fathers of children with

autism reading this a happy Father’s Day.

I know it isn’t easy, and if your child can’t thank you, please accept

my thanks on their behalf for standing by them.

Steven Kantor is a founding Board

Member of New York Collaborates for Autism. He resides in New York City with

his wife and two sons.

Leave a Reply