by Michael John Carley, NEXT for AUTISM Board Member

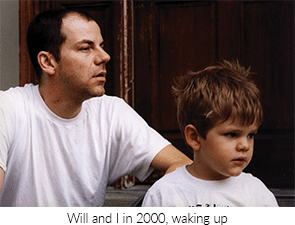

As many people know, my son Will and I were diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome within a week of one another in late 2000, when Will was four. What some may not know, however, is that two days after my diagnosis, I figuratively stabbed him in the back. Talking with a colleague in an elevator, I was telling her all about Will’s diagnosis, yet I neglected to mention mine. “Wow,” the colleague said, “but isn’t that stuff genetic?”

“Well, uh, not really,” I incoherently sputtered, “…don’t think so…”

How would I ever be able to say to him, “You should be proud of who you are,” if I was such a coward that day?

I immersed myself in the study of autism and what it meant for my son and me. A turning point came when I came across a fellow parent who was crying because his child flapped his arms in public. Reminded by worse things that I saw while working at an NGO in Iraq, I wanted to shake him and say, “Your child is alive. Shut up and love it.” But instead, I knelt beside him and whispered gently, “So what?”

Around that time, my friend and fellow spectrum author, Liane Holliday Willey, was the target of an article that said people on the spectrum had no business being parents. She’s a fabulous mother, and she was naturally upset. Guess what I told her? So what?

When you’re on the spectrum, you certainly need to find pockets to be who you are, as opposed to who others expect you to be. We all feel like that sometimes. But trust me, the need gets a major boost when you live on the spectrum. Too often, fearful of what could happen to our spectrum children, we over-emphasize the dangers, and forget to teach our kids the disregard that is equally necessary. This is what I try to teach my boys. It’s a lesson that I had adopted as a kid, long before our diagnoses.

My mother hated Father’s Day. Back then, there was a lot of stigma surrounding fatherlessness and single-motherhood. My situation as an outcast was heightened by the circumstances we lived under. My father, a Marine Corps helicopter pilot, had been killed in the Vietnam War. For a period of time, I was essentially a street kid. I learned early in life that being different means you have to sometimes just say, “So what?” Sometimes people sense our disregard for their concerns, and are rightfully insulted. But it sure beats the low self-esteem created by apologizing when you don’t know what you’re apologizing for.

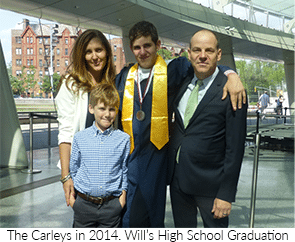

My son Will soon turns 21; he’s a man now. Like other kids, he has been at turns passionate, dramatic, outrageously funny, sad, a withholder and an illuminator of truth, a genius and a knucklehead. But maybe unlike others, Will is beyond loyal, and he has a positive energy in public that will never go unnoticed.

Despite my work as an autism activist, Will has liked his freedom from the cause. Someone remarked that watching us talk about autism was like watching Gloria Steinhem with a daughter who just wanted to listen to Brittany Spears. Where I see identity, he often sees pathology. Or in his words, “Dad, I have no desire to win any ‘Aspie of the Year’ awards.”

I am no great father. But thankfully, both boys have always been polite, gregarious, and great students, who are first and foremost, humanists. It didn’t take a parental arm and a leg to get them there. They make me look good.

But part of why I know not to pat myself too much on the back has to do with the shareddiagnosis. If anyone were to ever call Will rude, I would know he didn’t intend to be rude, and so would put my arm around him and say, “I know you didn’t mean to be rude.” Neurotypical parents hope that their spectrum child can be happy. But in hope, there is still so much doubt and anxiety. Me? I know that he—and his brother—can be happy. I am proof of that. And proof is very different from hope.

I miss Will now that he’s in college. He and his brother are tight. Their combined laughter is the greatest sound I’ll ever know. They share the same interests and admire each other. Will marvels at his brother’s skills. When a parent in the hockey stands would yell something negative about Bo (who can be a bruiser), Will would get upset and want to deck that parent. It was awkward, not Hollywood, but more loving and real as a result.

Bo was recently hailed at school for stopping a bully’s attempt to punch a frailer classmate—he literally caught the other kid’s moving fist in his hand, like one would a tennis ball or a yo-yo. “There will be no punching here,“ he said, as he held the other kid’s fist.

Bo knows that his older brother has had to work harder than most. He knows that things come easier to him. But he also knows that Will finished his high school baseball career as co-MVP on a league championship team,having not lost a start since his freshman year. Bo is proud that his brother won a full academic scholarship to a really good college. The fact that my kids are proud of each other is the best work that I’ve done as their Dad.

*****

On Father’s Day, Kathryn will make me breakfast. I’ll get a great card from Bo and a great phone call from Will. I know that Father’s Day is commercially hyped with greeting cards, golf sets, and baked goods. But so what? I like it. I lost my father when I was 19 months old. I have always tried to make fatherhood twice as much fun, imagining—without tragedy—how much he would have enjoyed it, and I wish I had the words for how much that heals.

Sometimes our fun is at the rest of the world’s expense. And yeah, I kinda did stab Will in the back that day. But dare I say? I think Will would agree with me.

So what?

Michael John Carley is the Founder of GRASP, a School Consultant, and the author of “Asperger’s From the Inside-Out,” “Unemployed on the Autism Spectrum,” and the upcoming “’The Book of Happy, Positive, and Confident Sex for Adults on the Autism Spectrum…and Beyond!” He also writes the Huffington Post column, “Autism Without Fear.” For more information please visit www.michaeljohncarley.com.

Leave a Reply